Springs, Caves, and the Underland: the Human Impact on our Planet

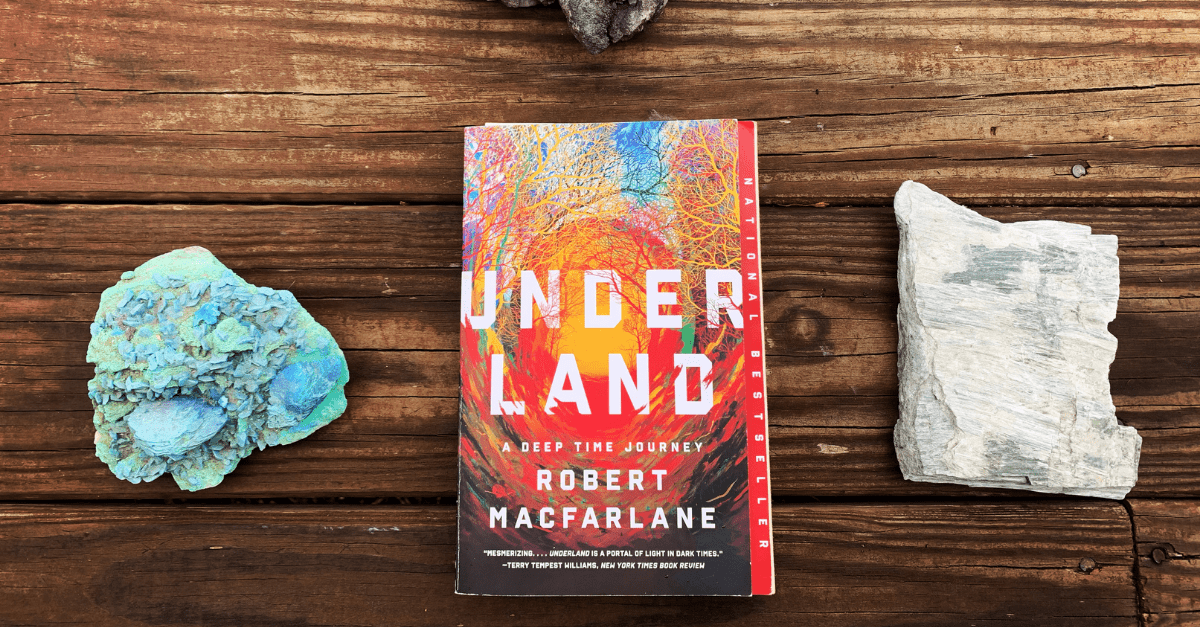

Robert Macfarlane’s 2019 book Underland took me on a journey through deep time. As someone who has always been fascinated by springs, caves and other underland spaces, I devoured this book — but not without a looming sense of unease at the human impact on these subterranean spaces and our collective future.

Macfarlane wrestles with the narcissism of the word ‘Anthropocene’, the era of human impact on climate and environment, and pulls Underland readers on a wild voyage underground, where time slows down and the past is not so easily disentangled from the present.

Come join us on Monday June 14th at 7:00 PM ET, even if you haven’t read this haunting book, for a virtual book club discussion on Underland! You can register here.

In our current times of mass extinction, rapidly escalating climate impacts and a warming tipping point in the not-so-distant future, wrestling with human impact on the land is necessary if we are to change the story. Macfarlane eloquently navigates the complicated nuance of the Anthropocene, noting that “there are many reasons to be suspicious of the idea of the Anthropocene. It generalizes the blame for what is a situation of vastly uneven making and suffering. The rhetorical ‘we’ of Anthropocene discourse smooths over severe inequalities, and universalizes the site-specific consequences of environmental damage. The designation of this epoch as the ‘age of man’ also seems like our crowning act of self-mythologization — and as such only to embed the technocratic narcissism that has produced the current crisis. But the Anthropocene, for all its faults, also issues a powerful shock and challenge to our self-perception as a species. It exposes both the limits of our control over the long-term processes of the planet, and the magnitude of the consequences of our activities. It lays bare some of the cross-weaves of vulnerability and culpability that exist between us and other beings now, as well as between humans and more-than-humans still to come.”

The reader embarks on thrilling descents into the Paris catacombs, a great and terrifying underground river, a deep blue glacier, nuclear waste storage facilities with lifespans far beyond our time, and the mythic resonance of ancient sites that are still very much alive today. Macfarlane implores, “at its best, deep time awareness might help us see ourselves as part of a web of gift, inheritance and legacy stretching over millions of years past and millions to come, bringing us to consider what we are leaving behind for the epochs and beings that will follow us.”

Macfarlane weaves his signature prose to transport the reader underground. He writes of an eerie opening to the underworld in Darvaza, Turkmenistan, where “the void migrates to the surface…The drilling has punctured a natural-gas cavern, the cavern’s roof has collapsed, and now poisonous fumes are pouring into the upper world. The decision is taken to ignite the gas and burn it off. It is expected that this will only take a few weeks. More than four decades later, the pit is still on fire. It has become known as the ‘Door to Hell’ and ‘Hell’s Gate’. At night its orange flames light up the desert for miles around.”

These portals to the ‘underworld’ that always reside below us house joyful as well as sorrowful presences. Macfarlane felt the warmth of those who created ancient rock art, recalling how “the sea eagle gyres by the cliff. The waves crash on the boulders below the cave. The Maelstrom spins and unspins. The hands of the dead press through the stone from the other side, meeting those of the living palm to palm, finger to finger…Time proceeds according to its usual rhythms beyond the threshold, but not here in this thin place.”

In regards to the stranglehold that oil currently holds on our world, Macfarlane finds the root of the powerful and greedy’s insatiable desire to plunder the subterranean realms. Macfarlane references Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘A Descent into the Maelstrom’ and viscerally describes Poe’s imagining of the swirling, ebony innards of a Maelstrom, a powerful whirlpool that can form on the ocean. In ‘Descent’, Poe writes of being hypnotized by the allure of the unknown depths and power of the maelstrom, wherein Macfarlane smartly describes that “Poe’s story and others like it speak in part of the mid nineteenth-century dreams of the ‘oceans of oil’ that were imagined to exist under the earth. These narratives advanced the Holocene delusion of a planetary interior containing inexhaustible wealth and energy — a delusion that still characterizes expansionist oil discourse, nearly two centuries after Poe was writing.”

Amidst all the darkness of the underlands, there is also the life-giving water of springs that come up mysteriously from the underground. Macfarlane remarks on the wonder, saying “springs astonish me, as springs always do. This is water that fell first as rain on high ground, then made the long journey through the underland, to emerge here — filling pool after pool with its energy and colour, before tumbling away seawards. Life has gathered around the springs. Groves of cypress and pine cast shade. Damselflies jewel leaves. The air is scored by birdsong. Emerald frogs plop into the water from the bank.”

Our own home state sits atop an incredible array of underground formations, caves, clear springs and karst terrain. As Macfarlane notes, “karst is vastly rich in its underlands — and it is also a terrain where water refuses to obey its usual courses of action. Karst hydrology is fabulously complex and imperfectly understood. In karst, springs rose from barren rock. Valleys are blind. A river can disappear in one place and appear in quite another, where it is given a new name by its new neighbors…Below the surface–if karst can be said to have a surface–aquifers fill and empty over centuries, there are labyrinths through which water circulates over millennia, there are caverns big as stadia, and there are buried rivers with cataracts, rapids and slow pools.”

Aside from the existential threats of climate change, our own karst terrain is under continued attack from projects like the fracked gas Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP). The MVP remains mired in litigation, it is lacking key permits, and there are over 600 waterbody crossings remaining in their woeful plan. This pipeline alone would emit nearly 90 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year (Oil Change International). If we are to heed Underland’s warnings, gas must never flow through this 42″ diameter monster of a pipeline. The MVP’s construction has already blasted through fragile karst terrain, ripped open caves that have carried water since time immemorial, and will continue to have a devastating effect on our very own ‘underlands’. These incredible formations have been here through deep time, providing the animate world with clear, cool water, habitat for thousands of species, natural filtration systems and spaces where the past mingles with the present. Do we want our legacy to the future to be wanton destruction of the ‘underlands’? As the reader finds in Underland, the underground world and the aboveground world are inextricably linked — and wrong done to one inevitably hurts the other.

Please consider joining us as a member to support our work and help stop the MVP from contributing to climate change while destroying our karst terrain, or consider coming to one of our events like Underland book club!