Habitat Connectivity is for Lovers

Driving down the road, the metallic odor of blood suddenly fills the van from the air conditioner. It’s a summer morning, and I’m an outdoor guide transporting 12 eager campers up a narrow mountain pass to the New River to spend the day kayaking. Turkey vultures take off in all directions as I veer around the shattered remains of a windshield. Spread across the road is the body of an elk.

Was the elk crossing the road, or is the road crossing the forest? 70,105 miles of Virginian roads divide large habitat expanses into smaller, isolated patches.1 This process of habitat fragmentation, slicing our wilderness into smaller pieces, threatens both ecological processes and public safety. Whether it is for food, mating, or refuge, Virginia wildlife must be able to move. Fragmentation, however, lowers overall habitat area and increases patch isolation. This forces species which migrate or require large ranges to cross dangerous interstates, imperiling both themselves and drivers. In what is known as the ‘edge effect’, species which require large swaths of habitat are disadvantaged while those which live along patch edges are favored. Together, this can lead to species extinction, improper nutrient cycling, and even reduced pollination.2

Fragmentation effects propagate through the whole ecosystem. Source: Haddad et al. 2015

Altogether, habitat fragmentation impacts both Virginia residents and our wildlife. However, these fragments are not beyond repair, and many can still be reconnected.

3 Reasons Why Virginia Should Support Habitat Connectivity:

1. Habitat Connectivity Protects Wild-lives and Human-life.

Animal-vehicle collisions endanger both animal and human lives. Considered a high-risk state, Virginia is ranked the 13th most dangerous state for animal-vehicle collisions with a 1 in 72 chance of a collision.3 These frequent animal-vehicle collisions, peaking during the Spring and Fall, can result in injuries and death. These accidents are also costly. For deer collisions alone, more than 90% result in vehicle damage costing about $1,840 per collision.3 Furthermore, especially on two-lane back roads on which deer are known to loiter, drivers will alternatively swerve to avoid a collision. This sudden change in direction poses the risk of a loss-of-control crash off the road, into a barricade, or even a head-on collision with an oncoming car.4 This phenomenon is particularly relevant with younger or more inexperienced drivers, who instinctively veer rather than brake.

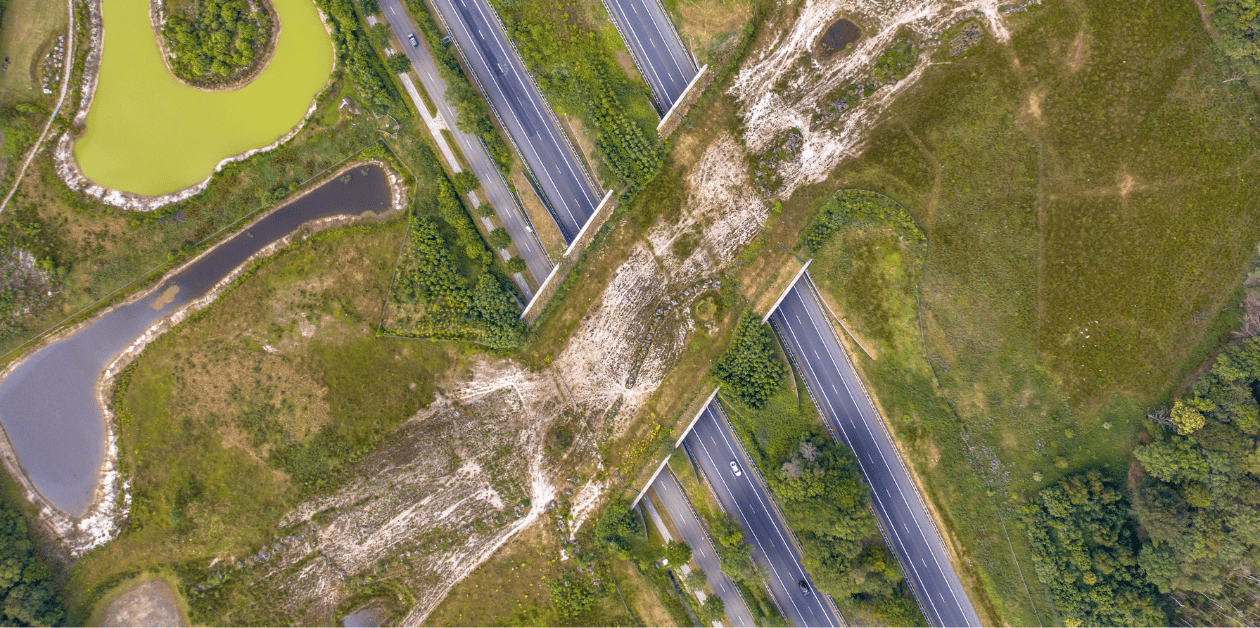

Wildlife corridors and crossings are successful connectivity strategies that simultaneously permit species movement while reducing such animal-vehicle collisions. Ecological corridors are intact pieces of habitat conserved to allow movement between two larger areas. Crossings, meanwhile, are human-constructed, and can be bridges or tunnels connecting bisected habitat. Although distinct forms of connectivity, both corridors and crossings can be implemented in both urban and rural settings.

Wildlife crossings, in particular, are incredibly successful at reducing animal-vehicle collisions. Overpasses or underpasses with fencing have reduced elk and deer vehicle collisions by 80-90% in the United States.5 By identifying wildlife corridors and targeting hotspots of wildlife crashes, Virginia can strategically implement crossings to maximize their benefits. If constructing an entirely new wildlife crossing isn’t affordable, simply enhancing key underpasses with fencing can dramatically reduce animal-vehicle collisions. Animal-vehicle collisions cause over 260,000 accidents, 12,000 human injuries, and over 150 deaths annually across the United States.6 Therefore, an investment in habitat connectivity is an investment in life.

2. Habitat Connectivity is Feasible.

As diverse as the species which rely on them, habitat connectivity solutions can be realized in various ways. Even if you aren’t familiar with the full ins and outs of habitat connectivity, you’ve probably at some point encountered a wildlife crossing or were familiar with the concept of a bear-bridge. But, just as it isn’t limited to terrestrial animals, habitat connectivity is not just bridges or tunnels. Habitat fragmentation impacts aquatic, avian, and even insect movement. Consequently, there exists an entire toolbox of habitat connectivity solutions which are adaptively applied to specific habitats, times of year, and species. By creatively reframing what habitat connectivity can be, solutions become more biologically inclusive and achievable through smaller-scale public participation.

In Virginia, we are home to about 80 species of mussels which perform crucial ecological services. The most endangered class of organisms, one mussel can filter up to 15 gallons of water a day, effectively filtering out pollutants such as nitrogen runoff from agricultural sources.1 In the Chesapeake Bay, 90% of freshwater mussel populations have been lost due to contamination and habitat fragmentation. Mussels, which rely on fish populations to carry their larvae upstream to be hatched, are impeded by dams and prevented from reaching hatching zones. Replacing crossing impediments such as dams or pipes with Aquatic Organism Passage (AOP) Structures provide a remedy. These underpasses and culverts permit the natural passage of aquatic species upstream and downstream.

Examples of Aquatic Organism Passages. Source: Great West Engineering.

Pollinators, and thus Virginia flora, also rely on habitat connectivity. Every fall, eastern monarch butterflies migrate south from North America to overwintering sites in Mexico and southern Florida. In the spring, they return northwards. Unfortunately, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) officially classified the monarch as endangered in July of 2022.8 Citizen-science provides data at the forefront of understanding this complex, widespread migration. Monarch tagging events are now popping up throughout the monarch’s range, wherein volunteers capture, tag, record, and re-release monarchs. Volunteer tracking efforts provide information on monarch origins, migration time and speed, mortality rates, and changes in geographic distribution. This information is made publicly available in wider databases such as MonarchWatch, essential to our current understanding of monarch butterflies. Through this monarch tracking data, we gain a better temporal and geographic understanding of their migration patterns, location of overwintering sites, and primary breeding grounds. With this information, we can conserve and maintain connectivity between sites of high importance for future monarchs, such as the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in Mexico. At Wild Virginia’s own monarch tagging event this September, the tagging was both engaging and informative, interwoven with wildlife conservation education. Organized by Habitat Connectivity Director Courtney Hayes, residents around Charlottesville met at a local Rockfish Valley Foundation Natural History Center. Provided with butterfly nets and tagging stickers, participants received a memorable experience, up-close look into the life of a monarch, and helped improve science’s grasp of monarch migratory patterns.

Wild Virginia Monarch Tagging Event. Source: WildVirginia.org

On a local level, interspersed pollinator gardens are essential in connecting larger habitats to enable movement of pollinating insects from one expanse to another. This movement is essential to pollinator survival and promotes genetic diversity through cross-pollination. In Seattle, the volunteer-organized Pollinator Pathway project attempts to defragment pollinator habitat by establishing a series of gardens to create corridors for bees, hummingbirds, and butterflies. Acting as pollinator ‘stepping stones’, these gardens are aimed to be about 750 meters apart, the range of most native bees. They can come in many forms, from revamped road medians, to formal backyard gardens, or even reimagined vacant lots. In Virginia, we can protect our native honeybees and butterflies by identifying pollinator hotspots and the potential interferences between them. Then, through the coordinated efforts of neighborhoods and communities, we can feasibly construct these pollinator pathways in our own road medians and gardens.

Pollinator pathways in Seattle. Source: PollinatorPathway.com

3. Human Connectivity Fosters Attunement to Nature and Eachother

Habitat connectivity induces a unique human attunement to nature by encouraging us to perceive habitats not as disparate pieces, but as essential interacting parts of a wider ecosystem. Experiences in nature have been shown to increase pro-environmental human behavior and a desire to protect it.9 However, increased spatial disconnect between us and our environment has limited both the opportunity and desire for this exposure. To combat this detachment, “[s]mall, humble habitats, especially in urban settings, can be as important as big reserves”. For example, in the construction of pollinator gardens in vacant lots, communities must first understand their regions native pollinators, their associated flora, and the conditions that flora requires to grow.

When we learn to identify habitat fragmentation in our communities, we become simultaneously exposed and tied to our land. Did you know that Virginia is 10th in overall vertebrate native species diversity and 8th in globally rare animals? That our very own Clinch and Powell rivers are the nation’s leading aquatic diversity hotspots? That, in Southwest Virginia, the Southern Appalachian Mountains were identified by the Nature Conservancy and NatureServe as one of six biodiversity hotspots in the entire United States.11 In our daily lives, this uniquely Virginian biodiversity surrounding us is often forgotten.

In Charlottesville, every year in late February, there is a spotted salamander population located near Polo Grounds Road which crosses the road in an annual trek back to their pond to reproduce. An event that has occurred for millennia, today about half of these salamanders are estimated to be crushed by passing cars. However, although the road is seeing increased traffic, the issue has been recognized by community members. Volunteers have begun assisting the salamander crossing by picking them up or shooing them across. In addition to a 300-acre development plan with 700 residences, the developer, Riverbend Development, intends to construct an amphibian underpass to allow the salamanders to cross. The salamander has even been proposed as the mascot of the elementary school within the development. Riverbend has also suggested installing “Mander Cams”, in order to livestream the annual crossing.12

Spotted Salamander. Source: Harris Center for Conservation Education

In addition to human-nature attunement, achieving habitat connectivity often requires collaborative, creative, and locally-based events which foster human-human connectivity. As with the Charlottesville salamander crossing and Wild Virginia’s monarch tagging events, habitat connectivity brings people together on what is literally common-ground to pursue something beneficial to both the human and ecological communities. These events, tied closely to the land, are unique in their common requirement of one’s physical presence. They can also be educational, generating an intimate, knowledgeable connection of community members with their local habitats.

Habitat fragmentation is something that we will need to contend with, especially as development progresses and climate change continues to shift species ranges.

As much as the elk collides with your front bumper, you collide with the elk.

But connectivity is not a daunting nor intimidating venture. Solutions come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and can be implemented at the state-, community-, or individual-level. From bear-bridges to salamander crossing brigades, solutions are as diverse as their habitats.

Furthermore, as much as we reconnect nature, we reconnect to nature. Habitat connectivity provokes a deeper awareness and relationship between humans and the natural world. By attending a salamander brigade, one ultimately comprehends that this annual migration has endured millennia. Through the catch-and-release of a monarch butterfly, a child comes to the humbling realization that we are inherently connected to Mexico. Through the creation of a pollinator garden, one must familiarize themselves with the unique pollinator food web of their region.

By enhancing small corridors, advocating for larger crossings, and volunteering at connectivity events we can all contribute to re-connectivity. In doing so, we defragment not only the biodiversity of Virginia, but also our communities and our personal roots in nature.

.

Sources

- https://vcnva.org/agenda-item/investing-in-wildlife-crossings-habitat-connectivity/

- https://natureneedshalf.org/2018/07/connectivity-for-biodiversity/

- State Farm. How Likely Are You to Have an Animal Collision? 2020. https://www.statefarm.com/simple-insights/auto-and-vehicles/how-likely-are-you-tohave-an-animal-collision. Accessed October 15, 2022.

- Hu, M., & Li, Y. (2017, October). Drivers’ avoidance patterns in near-collision intersection conflicts. In 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- https://www.virginiadot.org/vtrc/main/online_reports/pdf/20-r28.pdf

- https://www.havahart.com/wildlife-on-the-road

- https://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks-facilities/burnham-wildlife-corridor

- https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/monarch-butterfly

- Clayton, S. D., & Myers, G. (2015). Perceptions of environmental problems. Conservation Psychology: Understanding and Promoting Human Care for Nature,(Chichester, West Sussex, UK: WILEY-Blackwell), 114-129.

- Pyle, R. M. (2003). Nature matrix: reconnecting people and nature. Oryx, 37(2), 206-214.

- http://www.landscope.org/virginia/plants-animals/Species%20101/#:~:text=When%20compared%20with%20other%20states,and%2013th%20for%20vascular%20plants.

- https://dailyprogress.com/a-salamanders-tunnel-of-love/article_16f5fda7-7836-59de-9912-ea0af52267ba.html