Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Connectivity

by Allie Lowy

“Is the deer crossing the road, or is the road crossing the forest?” – Freequill

Αn insurance company analyst, Master Naturalist, Department of Transportation employee, and conservation biologist walk into a bar. What do they have in common?

Now that I have your attention, it was not a bar, but, rather, the meeting room of a public library — and, on July 17, I found myself in that very room.The four were gathered as part of the Virginia Safe Wildlife Corridors Collaborative (VSWCC) — a nascent group formed to reduce animal-vehicle collisions on roads and provide safe passages for wildlife. Bringing together groups like the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT), the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, the Highway Loss Data Institute, and conservation groups like the Wildlands Network and Wild Virginia, VSWCC takes a multi-stakeholder approach to a complex, multi-disciplinary issue in road ecology.

Who is the Collaborative?

The Collaborative includes an analyst from Highway Loss Data Institute, who provides insurance companies with crash data; a conservation biologist from William & Mary, who does GIS mapping of animal habitat near interstates; a veterinarian from the Wildlife Center, which cleans up the carnage from crashes; an employee of VDOT — who researches animal passageways and measures to mitigate wildlife crashes; and Wild Virginia Director Misty Boos. Also involved are members of the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, which releases statewide Wildlife Action Plans to determine the species of greatest conservation need in Virginia; the coordinator of the Virginia Master Naturalists Program, which provides training in ecology, animal and plant identification, and the scientific method; and a member of the Wildlands Network, which works to promote habitat connectivity, the Collaborative’s bigger-picture goal.

Connectivity

In the modern age, animal core habitats have become increasingly fragmented. Due to human construction, land mammals move two to three times less than they used to, which means a limited ability to mate, feed, and migrate. Coupled with the fact that fragmentation reduces species richness and nutrient cycling, and climate change forces relocation, the threat of species extinction looms more ominously.

A widely-accepted connectivity strategy that supports species migrations is building wildlife corridors. Corridors can vary in shape, scope, and the species on which they focus, but they all seek to connect protected areas of habitat. Currently, only half of protected habitats around the world are connected.

As stated on the Wildlands Network website: “Connecting wildlife habitats is critical to conserving biodiversity in the face of climate change, which will increasingly trigger geographical shifts for wildlife populations, plant communities, and ecological processes.”

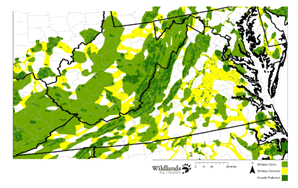

The Wildlands Network spearheaded the Eastern Wildway Initiative, which seeks to create a continuous unobstructed stretch of wildlife habitat along the East Coast, from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico. This wildway would contain some of the country’s most beloved wild places, from the Adirondacks to the Shenandoah Valley to the Great Smoky Mountains and Everglades National Park. The region harbors a wide range of climates, eco-regions and enormous biodiversity–in fact, the southeastern U.S. is one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. Wild Virginia is working to contribute to the Eastern Wildway as they work to improve habitat connectivity in Virginia.

Large Animal Crashes

The group’s primary concern is human safety, which is threatened by vehicle crashes with large animals like deer and bear. VDOT tracks bear and deer carcass data, and VDOT’s Bridget Donaldson has used this data to pinpoint hotspots for deer and bear crossings. According to Donaldson, deer make up 1 in 6 animal-vehicle collisions in Virginia, which puts the state in the top ten for deer-vehicle collisions nationally.

VDOT has begun building fencing to funnel animals into existing underpasses beneath large highways. On Interstate 64, 8 foot-high fencing now guides animals to a box culvert beneath the roadway and a bridge spanning a river. Cameras installed at the site show animals coming up to the fence, and turning around to find another way around, rather than crossing the interstate. It’s estimated that this is reducing crashes at a cost savings of $300,000 per stretch of fencing. The fencing includes jump outs: sections of fencing angled at the top to allow deer to pass one way — out of the road — but not the other. Recently, VSWCC has installed cameras in Buffalo Creek and Cedar Creek, which will be continuously monitored during November, deer breeding season.

At this point, you might be asking: why did the bear cross the road? But, in all seriousness, what is the biological impetus for large animals moving around so much? When mating, large-scale movement is crucial for genetic exchange and enhancing genetic diversity. Otherwise, inbreeding within the same area can hurt a species, reducing the biological fitness of a population.

Animals are naturally accustomed to moving around not only when mating, but when searching for food. Bear, whose food is scarce during winter months, must eat large amounts of food during the summer to survive, so they move constantly move to find it.

In the effort to reduce large-animal collisions, the Collaborative hopes Virginia will follow in the footsteps of other admirable states. In Montana, a 56-mile stretch of highway boasts 41 overpasses and underpasses for animals like deer, bear, coyotes, and bobcats. In Wyoming, underpasses for moose and elk and overpass bridges for pronghorn have reduced collisions tremendously. In Southern California, biologists have erected underpasses for the threatened desert tortoise, which long-tailed weasels and foxes have also benefited from. In Washington, squirrels cross over a major road on a narrow rope bridge between trees.

Outside of the U.S., the Netherlands has over 66 overpasses and ecoducts (wildlife bridges) to protect species like the endangered European badger, wild boar, and various species of deer. The Netherlands also boasts the longest wildlife overpass in the world, a half-mile long natural bridge which spans a railway line, park, roadway, and sports complex. In Australia, a bridge on Christmas Island helps 50 million red crabs migrate over a busy road.

Small Mammals and Herps

VSWCC also has a Small Mammals and Herps Working Group. One animal the Collaborative focuses on is salamanders, whose core habitat is the vernal pool, a type of wetland generally devoid of fish. When breeding, salamanders must migrate back to their vernal pools, which often means crossing roads. To curtail salamander-vehicle collisions, the Collaborative is looking to use drift fencing to guide salamanders through plastic tubes under interstates. Other states — like Massachusetts and Vermont — have had success with similar projects.

A mass migration of salamanders in Charlottesville has led volunteers to block off roads to aid their crossing, during which the majority of salamanders normally die. Because of volunteer efforts in February, the development company owning the road (Polo Grounds Road) agreed to construct a salamander tunnel underneath it later this year.

Fortunately, researchers in Vermont have mapped vernal pools across the entire North East (and included Virginia), which has aided in this mission.

The Small Mammals Work Group is also considering possible efforts toward the eastern spotted skunk (which is very slow) and the northern flying squirrel (whose habitats are often fragmented). It is also looking at ways to improve habitat connectivity diamondback terrapins at sites near the Virginia coast.

Goals for the Future

Moving forward, the group looks to influence public policy by making animal-vehicle collisions a priority for state lawmakers. According to VSWCC, policy must protect both core habitats for animals and the “corridors” that enable safe passage between them.

In 2016, a Virginia congressman introduced the Wildlife Corridors Conservation Act to the House of Representatives, which helped bring attention to the issue at the federal level. The Collaborative hopes to introduce a similar bill to the Virginia General Assembly in 2019.

VSWCC also hopes to follow other states’ lead in increasing opportunities for citizen science, creating systems for reporting animal crashes by taking photos, obtaining GPS coordinates, and collecting user data about animal carcasses on roads. The Collaborative’s next meeting is October 15. Hopefully, the Collaborative will soon have opportunities for volunteer involvement. In the meantime, keep your eye out for roadside critters on your daily commute!