Push to Protect Diamondback Terrapin as Endangered Species

The diamondback terrapin was once so closely associated with Maryland that the state’s leading university adopted the terp as its mascot, and it holds the title of the official state reptile. In Virginia, it is illegal to collect diamondback terrapins for commercial or personal use.

However, this species has encountered significant challenges, initially from overharvesting for food and more recently due to drowning in crab traps. The Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) has joined forces with 20 other organizations to advocate for Endangered Species Protection for the diamondback.

This coalition, which includes regional organizations like Assateague Coastal Trust and Wild Virginia along with national nonprofits, submitted a petition to NOAA Fisheries last month, seeking protection for the diamondback across its coastal marsh habitat from Massachusetts to Texas.

These creatures also are prone to habitat connectivity issues as females transition to land to lay eggs, their paths fragmented by roads.

According to CBD, the Chesapeake Bay is “likely the most crucial location for diamondback terrapins across its entire 16-state range along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts.”

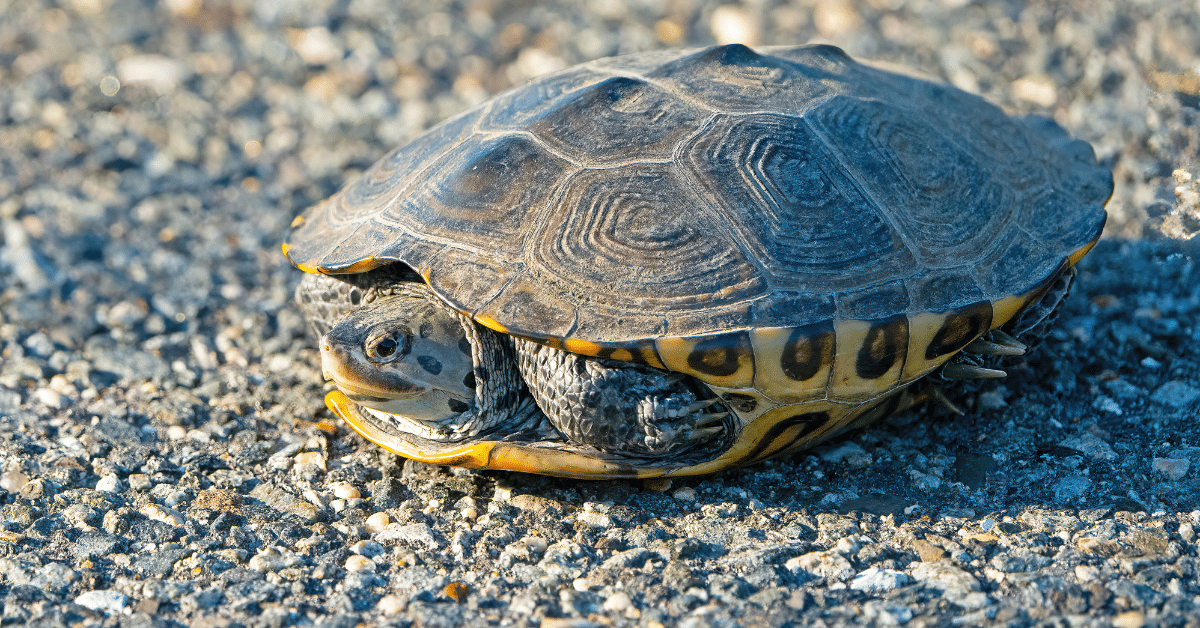

CBD reports that the terrapin population has plummeted by 75 percent over the last 50 years across most of that region. Known for its freckled body and unique diamond-patterned shell, the species was once a staple in the diets of Maryland and Virginia residents. As highlighted by a 1964 recipe from the Maryland State Archives, terrapins were commonly featured in a popular soup, akin to cream of crab soup.

Fishermen systematically depleted terrapin populations from various waterways, as outlined in the petition. Initially concentrated in Delaware Bay, the focus shifted to the Chesapeake after those stocks were exhausted. In Maryland, the terrapin harvest dropped dramatically from 40 metric tons to just 0.4 metric tons, representing only 1 percent of the previous yield. Eventually, harvesting efforts extended to Alabama and Texas.

Despite Marylanders gradually moving away from turtle soup, the species remained part of the state’s fishery until 2007, driven by increasing demand for turtle meat in Asia. In 2004, approximately 14,500 pounds of terrapins were harvested in Maryland alone, but this practice was ultimately banned by the state legislature in 2007.

Since then, habitat destruction has become a pressing concern, particularly due to shoreline development that damages or alters nesting beaches for terrapins. The petition refers to this issue as “shoreline armoring” and points out its severe impact in the Chesapeake Bay area.

Crab traps pose another significant threat, as turtles can become ensnared and drown inside, unable to surface for air. This issue is exacerbated by “ghost pots,” which are abandoned crab traps that turtles can inadvertently enter.

CBD estimates that between 60,000 and 80,000 terrapins die each year due to active and abandoned crab traps.

“Tens of thousands of terrapins are drowning in crab traps annually. Without the protective measures of the Endangered Species Act, they are on a path to extinction,” warned Will Harlan, a senior scientist at CBD.

Fortunately, a solution already exists and is being utilized by some watermen, though not sufficiently. Turtle excluders, or bycatch reduction devices, can decrease diamondback terrapin fatalities by 94 percent, according to CBD, without adversely affecting crab harvests.

In Maryland, Turtle Reduction Devices (TDRs) are mandated by law on crab traps. In Virginia, crabbing licenses cost an additional $10 if Terrapin Excluder Devices (TEDs) are not used on each pot. While their use is “strongly encouraged,” many still do not comply, leading to the continued decline of the Bay’s terrapin population.