Peakbagging for a Cause: Eric Gilchrist’s Conservation Journey

by Allie Lowy

On Wednesday, June 11th — a beautiful, sunny morning — at the top of Reddish Knob, I had the rare pleasure of meeting Eric Gilchrist. At 64 years old, Eric has spent the past two months ascending mountains on a mission: climb every peak in the George Washington National Forest (GWNF) over 4,000 feet. Eric’s environmentalism is deeply motivated by his passion for the outdoor spaces by which he is surrounded, which he feels a preservationist instinct to protect. Thus, Eric has dedicated his “peakbagging” project to Wild Virginia, asking friends and family to pledge money, all of which will go toward the organization. Of the 32 peaks in the forest over 4,000 feet, Eric has climbed 13, and raised $1,500 along the way. (You can pledge your donation to support Eric’s peakbagging the GW here.)

Most climbs have elevation gains of between 1,000 and 2,500 feet. Some of his favorite peaks thus far have been Freezeland Flats in Ramsey’s Draft Wilderness and the Switzerland-esque high-mountain meadow of Cole Mountain. Undoubtedly, his least favorite was the poorly-named “Big Knob,” which was only accessible via a road torn up by four-wheel drive vehicles.

Wild Virginia member Ernie Reed and I met Eric at the top of Reddish Knob, one of the highest points in Virginia, and a region steeped in history. Atop Reddish Knob, in 1999, Bill Clinton famously demanded that then-chief of the Forest Service Mike Dombeck craft a policy to protect unroaded areas in our national forests. This gave way to the 2001 Roadless Rule: a groundbreaking policy calling for protection of 58.5 million acres of roadless area within the national forests.

Years ago, Eric and Ernie set out to find the “wildest” place in Virginia: the region that is farthest from a road on all sides, that could be designated as wilderness. What they found was in the heart of Little River Roadless Area, a 27.3 thousand acre region of potential wilderness of which Reddish Knob is a part.

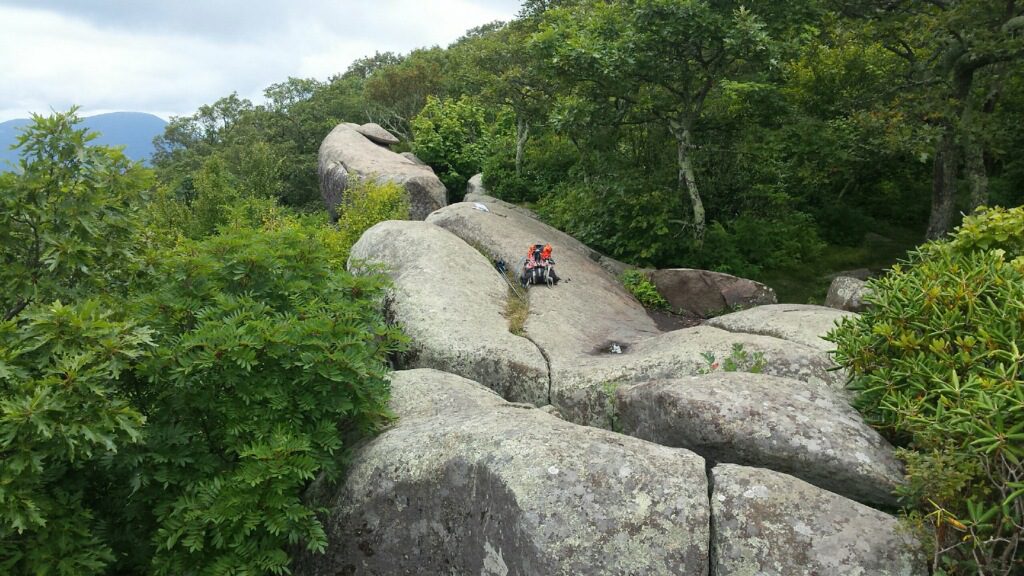

After meeting at Reddish Knob, the three of us peak-bagged Bother Knob, which gave me both a hearty sense of admiration for the fitness of my two hiking companions and a collection of nasty bush-whacking cuts on my bare legs. (That 40 extra years of wisdom Ernie and Eric have on me is really starting to make itself known.)

Talking to Ernie for any brief period of time is like dipping your toes into an unending pool of environmental knowledge, soaking up bits of passion along the way, remembering why you’re outraged and why you care so much. On this trip, it was particularly interesting to pick his brain about the absurdity of fracking policy. (Fracking — drilling into the Earth to extract gas and oil from shale — has had disastrous water quality and human health impacts, but, in 2005, president George Bush’s congress made it exempt from the Clean Water Act, the Safe Water Drinking Act, and the Clean Air Act, in what was famously termed “the Halliburton Loophole!”)

For a snack at the summit, Eric brought us his famous homemade pancakes made from banana, egg, cinnamon, and rolled oats.

Eric’s Story

Born in Staunton, Eric is a Central Virginia native, but he cites some of his first, most precious memories as exploring the Grand Tetons during his childhood in Idaho. After moving to Western Pennsylvania, Eric attained a B.S. in Man-Environment Relations from Penn State and went on to pursue an MBA there. After a 20-year stint as an account executive for large computer companies in the ‘80s and ‘90s, Eric longed to nurture his environmentalist roots. Upon returning to Central Virginia, Eric began volunteering for various environmental nonprofits. In 2002, he joined the board of the Shenandoah Ecosystems Defense Group, which now holds the catchier, less verbose title: Wild Virginia. On the board in 2002, he met Ernie, now one of his best friends, and the rest is history. After 12 years on the board, Eric resigned in 2014. Aside from Wild Virginia, Eric has done energy efficiency work in Charlottesville and helped found the Local Energy Alliance Program (LEAP), a nonprofit that conducts energy assessments and helps homes convert to solar energy. Eric also helped found Appalachian Sustainable Development, an organization that contracts with loggers to make available sustainable, locally-sourced lumber.

In the past decade, Eric has taken his sustainability to a new level through his latest project: building a completely eco-friendly house. Eric spent five years building an 800 square-foot house made entirely from wood harvested from right off his property, in GWNF. The small, cozy house is designed with a number of features that make it energy-efficient: it has no interior doors or hallways; triple-pane windows; a heavily-insulated roof deck; a metal roof; and the house is oriented toward the south. With windows on the south side, they get solar gain during the winter — heat is stored in thermal mass during day and released into the house in the evening. In the next couple years, Eric hopes to go off the grid. The house boasts a tiny wood stove, cabinets made from local wood, and radiant floor heating heated by a domestic water heater. In essence, this means that Eric’s family gets hot water for bathing and cooking from the same power source that heats the floor. The house’s walls are 12 inches thick, which means more thermal mass, modulating the indoor temperatures more evenly, and for longer periods of time.

Eric hopes to finish peak-bagging in October, after a brief interlude to vacation in Canada in August. What will Eric do next to save the planet? Only time will tell. In the meantime, I hope he cooks many more batches of healthy, homemade pancakes for those hard-working Wild Virginia interns.